Are You An Accredited Investor?

/I considered calling this post "What The Heck Is An Accredited Investor?" But unless you are hanging out with stock brokers, you probably don't even recognize the term. That's a problem, because the SEC's accredited investor rule often dictates what you are allowed to invest in and what sort of businesses can afford to ask you for an investment in the first place. The rule has kept our money flowing in certain directions since the aftermath of the Great Depression. And for the first time since then, we are seeing serious efforts made to change it. So what is it and why should it matter to you?

So, are you an accredited investor?

Accredited Investors are the holy grail of ambitious start-ups and private fund managers. If you fall in the Accredited Investor category, the SEC assumes that you can look after yourself (financially, anyway), so many of the careful protections they put in place to keep us all from being squirreled out of our money don't apply to the deals you can make. You would think, then, that you'd have to be very rich or very sophisticated to be an Accredited Investor. The fact is, though, that a lot of well-off but not necessarily "wealthy" people are starting to fall into this category. And it's hard to see where we get the idea that they are all that financially sophisticated.

There are two ways that someone usually qualifies as "accredited": 1. you have at least $1,000,000 in assets (not including your home), OR 2. you made at least $200,000 a year for the past two years and believe you will earn that much next year (the number is $300,000 if it's you and your spouse jointly). (SEC Reg D, Rule 501).

That first category pulls in quite a few retirees whose pension funds grew over the decades or who inherited retirement funds or property from their own parents. Some of these folks are very sophisticated about money. Most of them probably are not. And while earning $200,000 a year is a great thing, that's not exactly rare or a sign of financial sophistication, either. Sophisticated or not, though, if you are an accredited investor, private businesses, start-ups, hedge funds and other sometimes murky investments are out there looking for you.

Does That Mean I Can Invest In the Next Tech Start-up?

Why, yes it does—maybe. Your Accredited Investor status matters because it means companies can ask you to invest even if they haven't gone through the paperwork and review process that the SEC usually requires in order to sell an investment to the general public. This can be a very good thing. With SEC public investment filings costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, smaller but equally worthy companies often just can't afford to the process. Limiting themselves to accredited investors means that they still have to follow some basic laws related to what they tell you (and don't tell you), but they don't have to come up with the independent audits and elaborately detailed paperwork. Note, though, that this also means they don't have to make all of that information public for inspection. In other words, it's up to you to make sure you ask the right questions.

What Should I Ask?

You should always ask questions about any investment before handing over your money. But if you are thinking of investing in an unregistered investment as an accredited investor, it's up to you to avoid the Ponzi schemes and the half-baked business plans. You need to ask some extra questions:

1. Who is selling you this thing? Make sure you research the person or company selling you the investment. That might be the company you are investing in, but it might also be an advisor, a hedge fund manager or a broker. Every day the SEC brings charges against people selling fake investments or giving misleading information to investors. Not everyone is caught, but a lot of these names end up on publicly available databases. Start with FINRA's Broker Check site and the Investment Advisor Public Disclosure website to find out more about a broker or advisor;

2. How much will I be charged? A start-up probably won't charge you for giving them money, but a hedge fund definitely will. Be sure you understand any fees you are paying to buy the investment (keep in mind that there might be two layers of fees if there is a broker and a fund involved);

3. How long do I have to leave my money with you? Ask whether your money will be locked in for a period and under what conditions you could sell the investment to get out. Hedge funds almost always require you to leave your money in for a period of time to ensure the manager can follow her long-term strategy. If you invest in a start-up or private business, the only way out will be if someone wants to buy your stake—never a certain event!;

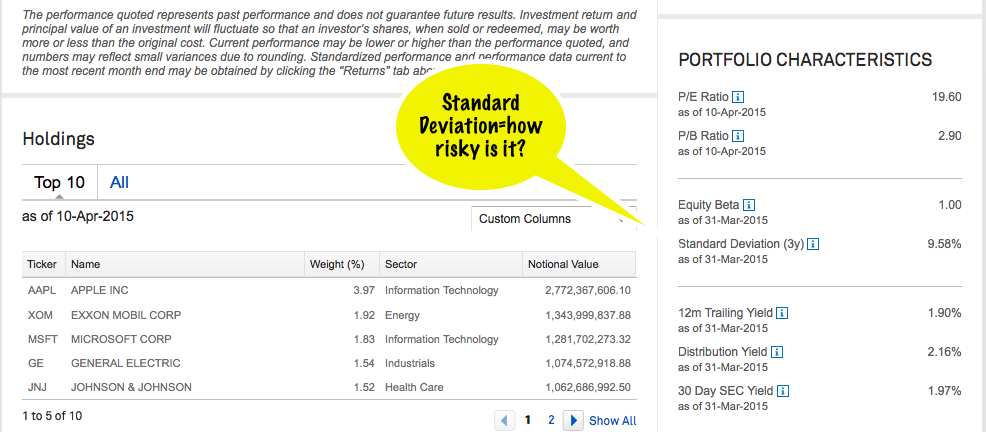

4. How will it make money? Be sure you understand the plan for making money. An investment fund should have a clear, understandable strategy for bringing in returns. A business should be able to show you reasonable (and readable!) estimates for when and how it will make a profit. Make sure you figure in the fees and liabilities to this calculation in case your broker/founder/fund manager doesn't;

5. What can go wrong? If someone tells you there is no risk to an investment, walk away immediately—no such investments exist. Make sure you understand all of the ways your investment could lose value so you can decide how comfortable you are with that risk;

If, after you've asked those questions, you still don't understand something, get an expert. Don't let company representatives, brokers or even your own advisor gloss over the important facts about what you are buying. If the expert in front of you can not make these things clear, or if you are worried that he or she has a conflict of interest, bring in another expert review the materials. Ask an accountant, attorney or financial advisor who is not involved in the deal review the particulars.

For more questions that every investor should ask, check out the SEC's online investor guide.